Part 1. Algorithm and Flow control with Python#

Algorithms and flowcharts#

Algorithms are step-by-step procedures or formulas for solving a problem. They are essential in computer science and programming, as they provide a clear set of instructions for performing tasks or computations.

Before writing any code, it is important to define the logic of your program. A good initial step when developing code is planning and structuring the logic before with a scheme or a flow chart. This involves thinking about the specific operations and functions you will need to implement, as well as the initial data required, and what the expected outputs will be.

Algorithms are the backbone of programming, as they define how a program operates and processes data. The more complex the task, the more important it is to have a well-defined algorithm to ensure that the program functions correctly and efficiently.

As a general rule, an algorithm should be:

Clear and unambiguous: Each step should be precisely defined.

Finite: It should have a clear starting and ending point.

Effective: Each step should be feasible and executable.

Input and Output: It should have defined inputs and outputs.

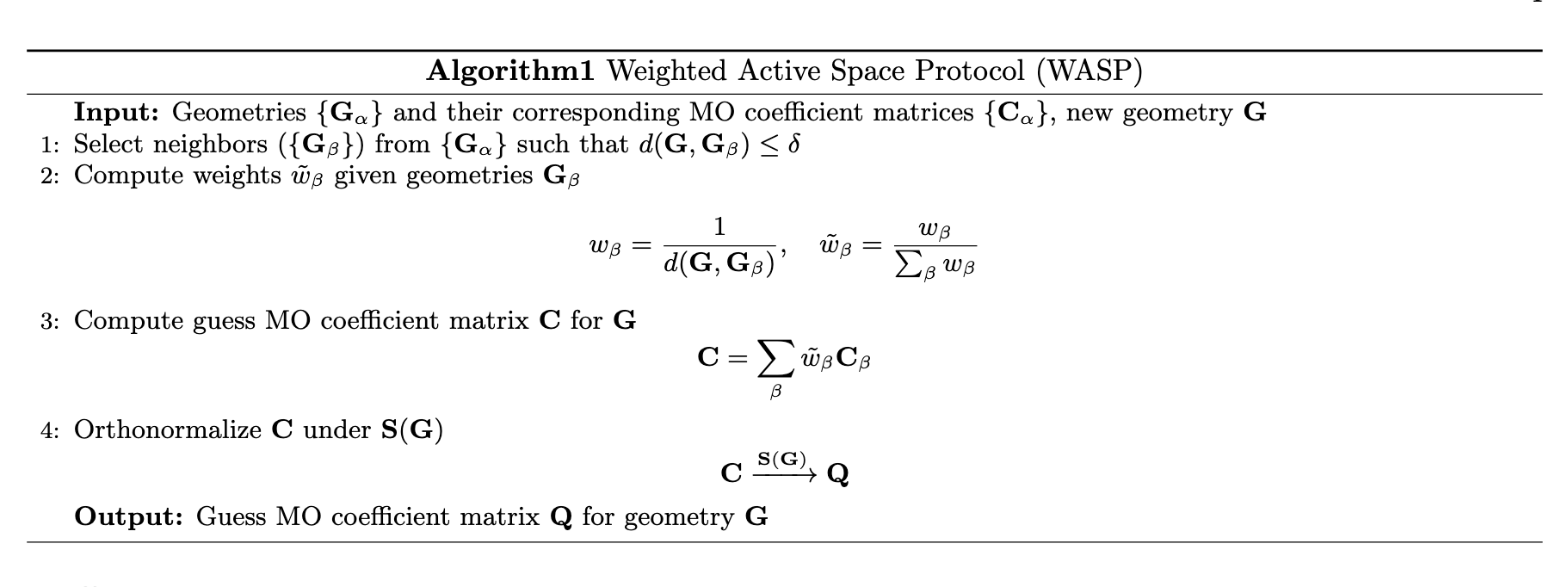

Here is an example of an algorithm’s basic scheme :

Algorithmic representation of the Wasp algorithm, extracted from https://arxiv.org/pdf/2505.10505; public repository available at GagliardiGroup/wasp)

Algorithmic representation of the Wasp algorithm, extracted from https://arxiv.org/pdf/2505.10505; public repository available at GagliardiGroup/wasp)

It is important to understand that an algorithm is not tied to a specific programming language; rather, it is a conceptual framework that can be implemented in various languages.

Tip

A good practise is to first think :

How your physical system is defined. Which are the characteristics of your system (eg, Hamiltonian, dimensionality, interconnections, …)

Then which will be initial data you need to start from (for instance, which variables you will need to define, in which units, transformations you will need to apply, which data you will need to read from external files, …),

and finally, which are the expected outputs (which are the outcomes, simulation trajectories, units in which they will be expressed, format of the data, if you will need to export it to an external file, …).

Once you have done that, you can start developing how will be the whole process. Which operations, functions or methods you will need to implement in order to get your expected output.

I strongly recommend to write down a very basic, simplistic, logic scheme (e.g., a flowchart or a list of steps) to help you plan how the analysis needs to be performed, and how to code it.

It is very likely that you will modify this scheme as you progress through the problem-solving process. But at least you will have a starting point to work from with a defined structure.

As you get familiar with programming, you will be able to do this step mentally, but at the beginning it is very useful to write it down.

Flowcharts are extremely useful to visualize the steps of an algorithm, for both in the initial planning stages and once it has been implemented.

Flowcharts use standardized symbols to represent different types of actions or steps in a process, and arrows to indicate the flow of control from one step to the next.

Here are some common flowchart symbols:

Terminator: Represents the start or end of a process. It is usually depicted as an oval or rounded rectangle.

Process: Represents a process or operation to be performed. It is typically shown as a rectangle.

Decision: Represents a decision point that can lead to different branches based on a condition. It is usually depicted as a diamond shape.

Input/Output: Represents an input or output operation, such as reading data or displaying results.

Arrow: Indicates the flow of control from one step to another.

Connector: Represents a connection point in the flowchart, often used to connect different parts of the chart or to indicate a jump to another section.

Loop: Represents a loop or iteration in the process, often shown as a circular arrow or a rectangle with a curved arrow.

Image by Arthur Baelde, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70282331

Short exercise : Draw a flowchart for the following algorithm to read a trajectory file with cartesian coordinates, then transform them to spherical coordinates to apply a 180° rotation, and finally write the results to a new file in cartesian coordinates again.

1.1 Indenting#

Python is known for its readability and simplicity. It is actually achieved because it employs indentation as a core aspect of its syntax to define these structures. It is basically in which order, instructions will be executed. An important aspect in Python is that it uses indentation to define blocks of code, which is crucial for maintaining the structure and flow of the program.

Indentation is a key feature in Python since it denotes blocks of code that belong together, such as the body of a function, loop, or conditional statement. In contrast to many other programming languages that use curly braces {} or keywords to define blocks of code, Python relies on indentation levels to indicate the grouping of statements.

You can either use tabs or spaces for indentation, but it is important to be consistent throughout your code. Mixing tabs and spaces can lead to errors that are difficult to debug. As a standard convention in the Python community is to use 4 spaces per indentation level. A good trick to maintain consistency is to configure your text editor or IDE to insert 4 spaces when you press the Tab key.

Examples :

if a == b:

# first level of indentation (within if statement)

for x in range(y):

# second level of indenting (within for loop and if statement)

if x > a:

# third level of indenting (within if statement within for loop

# within outer if statement)

...

Which of these three examples is right, and which one is wrong?

x = True

if x is True:

print("x is True")

if x is True:

print("x is True")

print("...or is it!")

if x is True:

print("x is True")

print("...or is it!")

The first two examples are wrong because they do not maintain consistent indentation levels. The first example lacks indentation for the print statement, and the second example has inconsistent indentation levels for the two print statements. The third example is correct because it maintains consistent indentation levels for both print statements within the if block.

Here is a more complete example of indentation, have a look at the different blocks:

def my_function(a):

# first level of indentation

x = range(a)

y = []

for i in x:

# second level of indentation

y.append(i * 2 + 1)

# back to first level of indenting (i.e., outside the for loop, but still in the function definition)

return y

# back outside the function definition

b = my_function(10)

print(b)

1.2 Conditional statements: if, elif, else#

Conditional statements are used to execute different blocks of code based on certain conditions. The most common conditional statements are if, elif, and else.

Before using conditional statements, it is important to understand boolean expressions. A boolean expression is an expression that evaluates to either True or False. These expressions are often used in conditional statements to determine which block of code should be executed.

Conditional statements are based on conditions that evaluate to either True or False based on conditionaal expressions.

Some conditional expressions include:

Equality:

==Inequality:

!=Greater than:

>Less than:

<Greater than or equal to:

>=Less than or equal to:

<=Membership:

in,not inIdentity:

is,is notLogical operators:

and,or,notBitwise operators:

&,|,^,~,<<,>>Ternary conditional operator:

a if condition else bChained comparisons:

a < b < cLambda functions:

lambda x: x > 0

For instance, you can use an if statement to check if a variable is greater than a certain value, and execute a block of code if the condition is True. You can also use elif (short for “else if”) to check multiple conditions, and else to execute a block of code if none of the previous conditions are True.

Here is an example of using if, elif, and else statements in Python:

x = 10

if x > 0:

print("x is positive")

elif x < 0:

print("x is negative")

else:

print("x is zero")

If Statements#

x = 5

if x > 0:

print("x is positive")

This code checks if x is greater than 0. This loops are based on boolean operations, either if something is true or false. If the condition is True, it prints “x is positive”.

#Feel free to experiment with the boolean value of the following condtions

Condition1 = False

Condition2 = True

a=1

b=2

#Notice the indented blocks of code, this indicates which code to be executed under the stated conditions

if Condition1: #If condition1 is true

a=a+b #do this

elif Condition2:#Else if condition2 is true

a=a-b #do this

else: #else if both conditions are false

a=a*b #do this

print(a)

-1

We can also nest conditional statements

Condition1 = True

Condition2 = False

if Condition1:

if Condition2:

print("Both conditions are TRUE")

else:

print("Condition1 is TRUE, Condition2 is FALSE")

elif Condition2:

print("Condition1 is FALSE, Condition2 is TRUE")

else:

print("Both conditions are FALSE")

Condition1 is TRUE, Condition2 is FALSE

Or the following does the same

if Condition1 and Condition2:

print("Both conditions are TRUE")

elif Condition1 and not Condition2:

print("Condition1 is TRUE, Condition2 is FALSE")

elif Condition2:

print("Condition1 is FALSE, Condition2 is TRUE")

else:

print("Both conditions are FALSE")

Condition1 is TRUE, Condition2 is FALSE

As does

if Condition1 and Condition2:

print("Both conditions are TRUE")

if Condition1 and not Condition2:

print("Condition1 is TRUE, Condition2 is FALSE")

if not Condition1 and Condition2:

print("Condition1 is FALSE, Condition2 is TRUE")

if not Condition1 and not Condition2:

print("Both conditions are FALSE")

Condition1 is TRUE, Condition2 is FALSE

It should be noted that we can ommit either/both elif and else as well as having as many elifs as we want.

Short exercise: Write a program that checks if a number is positive, negative or zero and prints an appropriate message to the user.

1.2 Try and Except#

Testing code is an important way to find out where the problems are. It is very easy to use the try-except block to catch and handle errors. If an error occurs, the code in the except block is executed.This is the basic syntax:

try:

# Some Code

except:

# Executed if error in the

# try block

Here is an example:

try:

# Code that may raise an exception

x = 3 / 0

print(x)

except:

# exception occurs, if code under try throws error

print("An exception occurred.")

Another example:

try:

x = 1 / 0

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("You can't divide by zero!")

try: # block of code...

print(hi) # this should be a string, otherwise we are calling a variable name that hasn't be assigned a value so a NameError will be given.

y = (1/0,5,7) # notice the 1/0 is not possible to compute and therefore a ZeroDivisionError error will be given

y[2] = 2 # y is a tupple wich cannot be changed so we will get a TypeError

except NameError: # executes variable's (or other object's) name is invalid

print('there was a name error')

except ZeroDivisionError: # executes when a division by 0 is found

print('there is division by 0')

except TypeError: # if we try to do something with a type that doesn't have that functionality

print('there was a type error')

except : # executes when a differnt problem found

print('there is a different problem')

else: # executes when no problem found

print('no problem found')

finally: # executes regardless of problem when block of code is finished

print('code is finished')

there was a name error

code is finished

Short exercise: Write a program that takes user input and handles potential errors using try and except blocks. For example, you could prompt the user to enter a number and handle cases where the input is not a valid number (e.g., if the user enters a string instead of a number).

try:

user_input = int(input("Please enter a number: "))

print("You entered:", user_input)

except ValueError:

print("That's not a valid number!")

1.3 While Loops#

A while loop is used to continuously execute a block of code as long as a certain condition is true.

count = 0

while count < 5:

print(count)

count += 1 # This is equivalent to add 1 to `count`

x=0

y=1

while x<100:

print(x)

x,y = y,x+y

0

1

1

2

3

5

8

13

21

34

55

89

1.4 Range and Zip#

The range class is very useful for loops as we will see next. Lets explore it, and see how we can use lists to visualise it.

list(range(5))

This gives us a list of numbers from 0 to 4. The range function can also take two arguments, a start and an end. The start is inclusive, the end is exclusive.

Warning

Remember that Python uses zero-based indexing, meaning that the first element of a sequence is at index 0. This is important to keep in mind when working with lists, strings, and other data structures in Python. Different programming languages use different conventions, so always check the documentation if you’re unsure. For example, in some languages like MATLAB, indexing starts at 1. And this can mess your code up if you don’t know it in advance!

stop = 10

x = range(stop)

print(type(x))

print(x)

#Now lets cast to a list and print so we can see what this looks like

x = list(x)

print(x)

<class 'range'>

range(0, 10)

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Notice that we get a sequence running from 0-9, not 0-10!! It is because the end is exclusive.

Syntax: range(start, end, step)

start = 10

stop = 40

step = 2

x = range(start, stop, step)

#We see range iterates from start to stop in increments of size step

print(list(range(start, stop, step)))

[10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38]

We see range iterates from start to stop - 1 in increments of size step.

It is useful to note the default vales of range(). If not given start is defaulted to 0 and step to 1.

print(list(range(10))) # if only one argument is given it is taken as "stop"

print(list(range(3,9))) # if two arguments are given it is taken as "start" and "stop"

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

[3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

Tip

When using range() in loops, remember that the end value is exclusive. This means that if you want to include a specific number in your loop, you need to set the end value to one more than that number. range(start, end+1, step)

The zip() function takes in two iterable data structures and returns an iterator of two object tupples as shown.

a = [1,2,3,4] # doesn't matter if these are tuples or lists

b = ('one', 'two', 'three')

c = zip(a,b)

print(type(c))

print(tuple(c)) # we can't directly print zip type objects so we cast them into a

#tuple (or list) to see their contents

<class 'zip'>

((1, 'one'), (2, 'two'), (3, 'three'))

Each item is paired with its corresponding item in the structures. The length of this new object is determined by the shortest list as seen. This is a very useful object when we iterate over two objects.

It can take several iterables as input, and it will return an iterator that aggregates elements from each of the iterables. The resulting iterator produces tuples, where the i-th tuple contains the i-th element from each of the input iterables. The iteration stops when the shortest input iterable ends.

names = ["Alice", "Bob", "Charlie"]

ages = [25, 30, 35]

cities = ["New York", "San Francisco", "Chicago", "Lisbon"] # Notice cities has an extra element

# Zipping three lists

for name, age, city in zip(names, ages, cities):

print(f"{name}, {age}, lives in {city}.")

Alice, 25, lives in New York.

Bob, 30, lives in San Francisco.

Charlie, 35, lives in Chicago.

Short exercise: Write a program that generates two lists, at least one using range(), both of equal length and uses the zip() function to iterate over them simultaneously, printing out pairs of corresponding elements from each list.

list1 = list(range(5))

list2 = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

for num, letter in zip(list1, list2):

print(num, letter)

1.5 For loops#

For loops are used to iterate over a sequence (like a list, tuple, dictionary, set, or string).

fruits = ["apple", "banana", "cherry"]

for fruit in fruits:

print(fruit)

L = [2,4,5,6,7,11,24,6]

for i in L:

print(i)

2

4

5

6

7

11

24

6

We saw the range function before, which is very useful when combined with loops

L = range(10,30,3)

for i in L:

print(i)

10

13

16

19

22

25

28

#The Fibonacci Sequence:

x=0

y=1

for i in range(1,20): # Notice that we start from 1 and go to 19 (20 is excluded)

print('Fib',i,':',x)

x,y = y,x+y

Fib 1 : 0

Fib 2 : 1

Fib 3 : 1

Fib 4 : 2

Fib 5 : 3

Fib 6 : 5

Fib 7 : 8

Fib 8 : 13

Fib 9 : 21

Fib 10 : 34

Fib 11 : 55

Fib 12 : 89

Fib 13 : 144

Fib 14 : 233

Fib 15 : 377

Fib 16 : 610

Fib 17 : 987

Fib 18 : 1597

Fib 19 : 2584

Sometimes we want to use both the placement of an object and the object itself. For this the enumerate() function is useful

words = ('first', 'second', 'third')

for i, word in enumerate(words): # notice the two

print(i,word)

0 first

1 second

2 third

We can also iterate over two objects, in this case, two lists, using zip()

a = [1,2,3,4]

b = ('one', 'two', 'three', 'four')

for i,j in zip(a,b):

print(i, j)

1 one

2 two

3 three

4 four

or using dictionaries, the keys will be iterated over. The .items attribute will allow you to iterate over both the keys and the values in a similar way to zip().

QM_Constants = {

'planck' : 6.62607015e-34,

'speed of light' : 299792458,

'pi' : 3.14159265359}

for i in QM_Constants: # will iterate over keys of the dictionary

print(i,'->',QM_Constants[i])

print('\n')

for i,j in QM_Constants.items(): # .items() makes the dictionary an iterator of two object tuples

print(i,'->',j)

planck -> 6.62607015e-34

speed of light -> 299792458

pi -> 3.14159265359

planck -> 6.62607015e-34

speed of light -> 299792458

pi -> 3.14159265359

Short exercise: Write a program that iterates over x, y, z coordinates of a 3D point stored in a dictionary and prints each coordinate with its corresponding axis label (x, y, z).

point = {'x': 1, 'y': 2, 'z': 3}

for axis, value in point.items():

print(f"{axis}: {value}")

1.6 Break, Continue, Pass#

The break statement is used to exit a loop prematurely when a certain condition is met.

for i in range(10):

if i == 5:

break

print(i)

This will print the numbers 0 to 4, and then exit the loop when i equals 5.

It basically stops a loop.

i = 0

while i==i:

print(i)

i=i+1

if i>5:

print("Uh oh! STOP!")

break # Stops a loop

print("I'm still iterating")

The continue statement is used to skip the current iteration of a loop and move on to the next one.

for i in range(10):

if i>=5:

continue # Moves us to the next iteration in the loop and ignores any code that follows

print("i is less than 5")

The pass statement is a placeholder that does nothing. It is often used in situations where a statement is syntactically required but no action is needed.

for i in range(10):

if i % 2 == 0:

pass # Do nothing for even numbers

else:

print(i) # This will print only odd numbers

Summary#

Algorithm and flow control design:#

Know the physical system you are trying to model and your input data to model it.

Know the algorithm’s goal, defining which are the expected outputs.

Think about the data types you will be using, and how to structure your data (e.g., lists, dictionaries, arrays).

Plan the logic, which operations you will need to implement.

Write a basic scheme or flowchart to help you plan how the analysis needs to be performed, and how to code it.

Implement the code, testing and modifying the workflow as you go.

Flow control statements:#

In this section, we have covered the basics of flow control in Python, including conditional statements (if, elif, else), loops (for and while), and control statements (break, continue, pass). These constructs are fundamental for creating dynamic and responsive programs that can make decisions and repeat actions based on certain conditions. An important note is to keep the indentation consistent, as it defines each block of code in your Python program.